List 2 Characteristics From the Following Art Erasetruscan Era

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported past the Etruscans, simply e'er retained distinct characteristics. Especially potent in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terra cotta (specially life-size on sarcophagi or temples), wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.[2]

Etruscan sculpture in cast statuary was famous and widely exported, merely relatively few large examples have survived (the material was besides valuable, and recycled afterwards). In contrast to terra cotta and bronze, there was relatively little Etruscan sculpture in rock, despite the Etruscans decision-making fine sources of marble, including Carrara marble, which seems not to have been exploited until the Romans.

The great majority of survivals came from tombs, which were typically crammed with sarcophagi and grave goods, and terracotta fragments of architectural sculpture, mostly around temples. Tombs have produced all the fresco wall-paintings, which show scenes of feasting and some narrative mythological subjects.

Bucchero wares in black were the early and native styles of fine Etruscan pottery. At that place was also a tradition of elaborate Etruscan vase painting, which sprang from its Greek equivalent; the Etruscans were the main export market for Greek vases. Etruscan temples were heavily busy with colourfully painted terracotta antefixes and other fittings, which survive in large numbers where the wooden superstructure has vanished. Etruscan art was strongly continued to organized religion; the afterlife was of major importance in Etruscan art.[3]

History [edit]

Relief mirror-back with "Herekele" (Hercules) seizing Mlacuch (500–475 BC)

The Etruscans emerged from the Villanovan culture. Due to the proximity and/or commercial contact to Etruria, other ancient cultures influenced Etruscan art during the Orientalizing menstruation, such as Hellenic republic, Phoenicia, Egypt, Assyria and the Centre East. The Romans would later come to blot the Etruscan culture into theirs only would too be greatly influenced by them and their fine art.

Periods [edit]

Etruscan fine art is unremarkably divided into a number of periods:

- 900 to 700 BC – Villanovan period. Already the emphasis on funerary art is evident. Impasto pottery with geometric decoration, or shaped equally hut urns. Bronze objects, mostly pocket-sized except for vessels, were busy by moulding or by incised lines. Small-scale statuettes were mostly handles or other fittings for vessels.[4]

- 700–575 BC – Orientalising period. Strange trade with established Mediterranean civilizations interested in the metal ores of Etruria and other products from further north led to imports of foreign fine art, especially that of Ancient Greece, and some Greek artists immigrated. Ornamentation adopted a Greek, and Near Eastern vocabulary with palmettes and other motifs, and the foreign king of beasts was a pop animal to depict. The Etruscan upper grade grew wealthy and began to fill their large tombs with grave goods. A native Bucchero pottery, now using the potter's wheel, went aslope the showtime of a Greek-influenced tradition of painted vases, which until 600 drew more than from Corinth than Athens.[5] The facial features (the profile, almond-shaped optics, large nose) in the frescoes and sculptures, and the depiction of reddish-chocolate-brown men and calorie-free-skinned women, influenced by archaic Greek art, follow the artistic traditions from the Eastern Mediterranean. These images accept, therefore, a very express value for a realistic representation of the Etruscan population.[6] It was only from the end of the 4th century B.C. that evidence of physiognomic portraits began to be found in Etruscan art and Etruscan portraiture became more realistic.[seven]

- 575–480 BC – Primitive menstruation. Prosperity continued to abound, and Greek influence grew to the exclusion of other Mediterranean cultures, despite the two cultures coming into disharmonize as their respective zones of expansion met each other. The flow saw the emergence of the Etruscan temple, with its elaborate and brightly painted terracotta decorations, and other larger buildings. Figurative art, including homo figures and narrative scenes, grew more prominent. The Etruscans adopted stories from Greek mythology enthusiastically. Paintings in fresco begin to be found in tombs (which the Greeks had stopped making centuries before), and were perhaps made for another buildings. The Persian conquest of Ionia in 546 saw a significant influx of Greek artist refugees, peculiarly in Southern Etruria. Other before developments connected, and the menses produced much of the finest and most distinctive Etruscan art.[8]

- 480–300 BC – Classical period. The Etruscans had now peaked in economic and political terms, and the volume of art produced reduced somewhat in the fifth century, with prosperity shifting from the coastal cities to the interior, especially the Po valley. In the fourth century volumes revived somewhat, and previous trends continued to develop without major innovations in the repertoire, except for the arrival of cerise-figure vase painting, and more sculpture such every bit sarcophagi in rock rather than terracotta. Bronzes from Vulci were exported widely inside Etruria and across. The Romans were at present picking off the Etruscan cities i by one, with Veii existence conquered effectually 396.[9]

- 300–l BC – Hellenistic or late phase. Over this period the remaining Etruscan cities were all gradually captivated into Roman culture, and, specially around the I century BC, the extent to which art and compages should be described as Etruscan or Roman is often difficult to judge. Distinctive Etruscan types of object gradually ceased to be made, with the last painted vases actualization early in the flow, and large painted tombs ending in the 2nd century. Styles continued to follow broad Greek trends, with increasing sophistication and classical realism often accompanied by a loss of free energy and graphic symbol. Statuary statues, now increasingly large, were sometimes replicas of Greek models. The large Greek temple pedimental sculpture groups of sculptures were introduced, but in terra cotta.[10]

Sculpture [edit]

The Etruscans were very accomplished sculptors, with many surviving examples in terra cotta, both small-calibration and awe-inspiring, bronze, and alabaster. Even so, there is very picayune in stone, in contrast to the Greeks and Romans. Terracotta sculptures from temples have nearly all had to exist reconstructed from a mass of fragments, but sculptures from tombs, including the distinctive form of sarcophagus tops with near life-size reclining figures, accept ordinarily survived in practiced condition, although the painting on them has usually suffered. Small-scale statuary pieces, oft including sculptural decoration, became an important industry in afterward periods, exported to the Romans and others. See the "Metalwork" section below for these, and "Funerary art" for tomb art.

The famous bronze "Capitoline Wolf" in the Capitoline Museum, Rome, was long regarded as Etruscan, its age is now disputed, it may actually appointment from the 12th century.

- The Etruscan Head, 600 BC, Archaeological Museum in Milan.

- The Centaur of Vulci, 590–580 BC, National Etruscan Museum, from the Villa Giulia

- the painted terracotta Apollo of Veii, 510–500 BC, from the temple at Portanaccio attributed to Vulca at the National Etruscan Museum

- the painted terracotta Sarcophagus of the Spouses, late 6th century BC, from Cerveteri at the National Etruscan Museum; there is a similar one in the Louvre

- the bronze Chimera of Arezzo, dated 400 BC, at the National Archaeological Museum (Florence)

- The Mars of Todi, a statuary sculpture from 400 BC in the Museo Etrusco Gregoriano of the Vatican

- The Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, 150–140 BC, a masterpiece of Etruscan art in terra cotta, at present at the British Museum

- The Orator, or Aule Metele ("Fifty'Arringatore" in Italian), bronze institute in Umbria at present at the National Archaeological Museum (Florence))

The Apollo of Veii is a good example of the mastery with which Etruscan artists produced these large art pieces. It was fabricated, along with others, to adorn the temple at Portanaccio'due south roof line. Although its style is reminiscent of the Greek Kroisos Kouros, having statues on the top of the roof was an original Etruscan idea.[11]

-

Etruscan pear woods head. 7th century BC

-

-

Naked youth, votive statuette. Bronze. Chiusi, 550–530 BC

-

-

Terracotta figure of a young woman, late 4th–early 3rd century BC

-

The Orator, Romano-Etruscan bronze statue, c. 100 BC

-

Statuary perfume container in the form of a deity with winged helmet

Wall-painting [edit]

The Etruscan paintings that accept survived are well-nigh all wall frescoes from tombs, mainly located in Tarquinia, and dating from roughly 670 BC to 200 BC, with the meridian of production between nigh 520 and 440 BC. The Greeks very rarely painted their tombs in the equivalent period, with rare exceptions such as the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum and southern Italian republic, and the Macedonian regal tombs at Vergina. The whole tradition of Greek painting on walls and panels, arguably the course of fine art that Greek contemporaries considered their greatest, is almost entirely lost, giving the Etruscan tradition, which undoubtedly drew much from Greek examples, an added importance, fifty-fifty if it does not approach the quality and sophistication of the all-time Greek masters. It is clear from literary sources that temples, houses and other buildings also had wall-paintings, but these have all been lost, like their Greek equivalents.[12]

The Etruscan tombs, which housed the remains of whole lineages, were apparently sites for recurrent family unit rituals, and the subjects of paintings probably have a more religious character than might at kickoff announced. A few detachable painted terra cotta panels have been establish in tombs, up to virtually a metre alpine, and fragments in city centres.[13]

The frescoes are created by applying paint on top of fresh plaster, so that when the plaster dries the painting becomes part of the plaster, and consequently an integral part of the wall. Colours were created from footing up minerals of different colours and were so mixed to the paint. Fine brushes were made of brute pilus.

From the mid quaternary century BC chiaroscuro modelling began to be used to portray depth and volume.[14] Sometimes scenes of everyday life are portrayed, but more often traditional mythological scenes, usually recognisable from Greek mythology, which the Etruscans seem largely to have adopted. Symposium scenes are common, and sport and hunting scenes are plant. The depiction of man anatomy never approaches Greek levels. The concept of proportion does not announced in whatever surviving frescoes and we often find portrayals of animals or men out of proportion. Various types of ornament cover much of the surface between figurative scenes.

-

Fresco in the François Tomb: Liberation of Celio Vibenna, from left to right: Caile Vibenna, Mastarna, Larth Ultes, Laris Papathnas Velznach, Pesna Aremsnas Sveamach, Rasce, Venthikau and Aule Vibenna, right: Marce Camitlnas et Cnaeve Tarchunies Rumach

-

Vase painting [edit]

Instance of Greek-style vase painting in Caere. Eurytus and Heracles in a symposium. Krater of corinthian columns called 'Krater of Eurytus', c. 600 BC

Etruscan vase painting was produced from the 7th through the 4th centuries BC, and is a major element in Etruscan art. Information technology was strongly influenced past Greek vase painting, followed the primary trends in style, especially those of Athens, over the period, simply lagging behind by some decades. The Etruscans used the same techniques, and largely the same shapes. Both the black-figure vase painting and the afterward red-figure vase painting techniques were used. The subjects were also very often drawn from Greek mythology in later periods.

Besides being producers in their own correct, the Etruscans were the master consign market place for Greek pottery outside Greece, and some Greek painters probably moved to Etruria, where richly decorated vases were a standard element of grave inventories. It has been suggested that many or about elaborately painted vases were specifically bought to be used in burials, as a substitute, cheaper and less likely to concenter robbers, for the vessels in argent and bronze that the elite would accept used in life.

Bucchero ware [edit]

More fully characteristic of Etruscan ceramic fine art are the glassy, unglazed bucchero terracotta wares, rendered black in a reducing kiln deprived of oxygen. This was an Etruscan development based on the pottery techniques of the Villanovan period. Often decorated with white lines, these may take eventually represented a traditional "heritage" way kept in use specially for tomb wares.

-

"Calabresi Ampoule", a fancy bucchero jug, 660–650 BC

-

-

Bucchero model "offering prepare" for a tomb, probably copying larger metal sets used in life.[15]

Terra cotta panels [edit]

A few large terracotta pinakes or plaques, much larger than are typical in Greek art, accept been found in tombs, some forming a series that creates in result a portable wall-painting. The "Boccanera" tomb at the Banditaccia necropolis at Cerveteri independent five panels most a metre high set round the wall, which are now in the British Museum. Three of them grade a single scene, apparently the Judgement of Paris, while the other 2 flanked the within of the archway, with sphinxes acting every bit tomb guardians. They appointment to about 560 BC. Fragments of similar panels have been found in city centre sites, presumably from temples, elite houses and other buildings, where the subjects include scenes of everyday life.[16]

Monteleone bronze chariot inlaid with ivory (530 BC)

Metalwork [edit]

The Etruscans were masters of statuary-working equally shown by the many outstanding examples in museums, and from accounts of the statues sent to Rome after their conquest.[17] According to Pliny, the Romans looted 2,000 bronze statues from the city of Volsinii alone after capturing it.[xviii]

The Monteleone chariot is one of the finest examples of large bronzework and is the best-preserved and most consummate of the surviving works.

The Etruscans had a strong tradition of working in bronze from very early times, and their small bronzes were widely exported. Apart from bandage bronze, the Etruscans were also skilled at the engraving of cast pieces with circuitous linear images, whose lines were filled with a white material to highlight them; in modern museum conditions with this filling lost, and the surface inevitably somewhat degraded, they are ofttimes much less striking and harder to read than would have been the instance originally. This technique was mostly applied to the roundish backs of polished bronze mirrors and to the sides of cistae. A major centre for cista industry was Praeneste, which somewhat like early on Rome was an Italic-speaking town in the Etruscan cultural sphere.[19] Some mirrors, or mirror covers (used to protect the mirror's reflective surface) are in a low relief.

Funerary fine art [edit]

The Etruscans excelled in portraying humans. Throughout their history they used two sets of burying practices: cremation and inhumation.[20] Cinerary urns (for cremation) and sarcophagi (for inhumation) accept been plant together in the aforementioned tomb showing that throughout generations, both forms were used at the same time.[21] In the 7th century they started depicting man heads on canopic urns and when they started burying their expressionless in the late 6th century they did then in terracotta sarcophagi.[22] These sarcophagi were decorated with an image of the deceased reclining on the lid alone or sometimes with a spouse. The Etruscans invented the custom of placing figures on the lid which subsequently influenced the Romans to do the aforementioned.[22] Funerary urns that were similar miniature versions of the sarcophagi, with a reclining effigy on the chapeau, became widely popular in Etruria.

The Hellenistic period funerary urns were mostly made in two pieces. The top lid usually depicted a banqueting man or woman (but non always) and the container part was either decorated in relief in the front end only or, on more than elaborate stone pieces, carved on its sides.[23] During this period, the terracotta urns were being mass-produced using clay in Northern Etruria (specifically in and around Chiusi).[24] Ofttimes the scenes decorated in relief on the forepart of the urn were depicting generic Greek influenced scenes.[25] The product of these urns did not require skilled artists and so what we are left with is often mediocre, unprofessional art, fabricated en masse.[26] All the same the color choices on the urns offering evidence as to dating, as colours used changed over fourth dimension.

-

Etruscan Cinerary Urn, mid-2nd century BC, terracotta – Worcester Art Museum

-

MMA Etruscan Funerary Urn

-

Etruscan Canopic Urn from Chiusi

-

Funerary Urn

-

-

A funerary urn with sculpture of a couple, from Bottarone, alabaster, early 4th century BC

-

Fine art and organized religion [edit]

5th to quaternary century BC necklace in gold

Etruscan art was often religious in character and, hence, strongly connected to the requirements of Etruscan religion. The Etruscan afterlife was negative, in contrast to the positive view in ancient Egypt where it was but a continuation of earthly life, or the confident relations with the gods as in ancient Greece.[ citation needed ] Roman interest in Etruscan organized religion centred on their methods of divination and propitiating and discovering the will of the gods, rather than the gods themselves, which may have distorted the information that has come downwardly to united states of america.[27] Virtually remains of Etruscan funerary art have been found in excavations of cemeteries (as at Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Populonia, Orvieto, Vetulonia, Norchia), pregnant that what we see of Etruscan art is primarily dominated by depictions of faith and in particular the funerary cult, whether or non that is a true reflection of Etruscan art as a whole.

Museums [edit]

Etruscan tombs were heavily looted from early on on, initially for precious metals. From the Renaissance onwards Etruscan objects, peculiarly painted vases and sarcophagi, were keenly collected. Many were exported earlier this was forbidden, and nearly major museum collections of classical art effectually the world have good selections. Only the major collections remain in Italian museums in Rome, Florence, and other cities in areas that were formerly Etruscan, which include the results of modernistic archæology.

Major collections in Italian republic include the National Etruscan Museum (Italian: Museo Nazionale Etrusco) in the Villa Giulia in Rome, National Archaeological Museum in Florence, Vatican Museums, Tarquinia National Museum, and the Archeological Civic Museum in Bologna, as well every bit more local collections almost of import sites such equally Cerveteri, Orvieto and Perugia. Some painted tombs, now emptied of their contents, tin be viewed at necropoli such as Cerveteri.

From September 2021 to June 2022, a major exhibition of Etruscan art is on show at the MARQ Archaeological Museum of Alicante, Espana.[28] The exhibition, Etruscans: The Dawn of Rome, features a large number of items on loan from the National Archaeological Museum, Florence and the Guarnacci Etruscan Museum in Volterra.[29]

Gallery [edit]

-

Gilt disc brooch, Cerveteri, 675–650 BC

-

Gold brooches

-

Gem with Herakles at Rest

-

Breast Ornamentation (?)

-

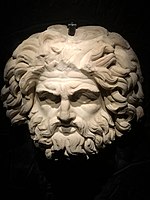

Caput of a god - MARQ exhibition of Etruscan art - March 2022

See also [edit]

- Etruscan compages

- Isis Tomb, Vulci

- Ombra della sera

- Tomb of the Augurs

- Tomb of the Bulls

- Tomb of the Dancers

- Tomb of the Leopards

- Tomb of the Triclinium

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Cista Depicting a Dionysian Revel and Perseus with Medusa's Head". The Walters Fine art Museum.

- ^ Boardman, 350–351

- ^ Spivey, Nigel (1997). Etruscan Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^ Grove, 2 (i)

- ^ Grove, 2 (ii); Boardman, 349

- ^ de Grummond, Nancy Thomson (2014). "Ethnicity and the Etruscans". Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Chichester, Uk: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 413–414.

The facial features, however, are not likely to establish a truthful portrait, just rather partake of a formula for representing the male in Etruria in Primitive art. It has been observed that the formula used—with the face in profile, showing almond-shaped eyes, a large nose, and a domed upwardly contour of the tiptop of the head—has its parallels in images from the eastern Mediterranean. But these features may evidence only artistic conventions and are therefore of express value for determining ethnicity.

- ^ Bianchi Bandinelli, Ranuccio (1984). "Il problema del ritratto". 50'arte classica (in Italian). Roma: Editori Riuniti.

- ^ Grove, 2 (3)

- ^ Grove, two (iv)

- ^ Grove, 2 (5)

- ^ (Ramage 2009: 46)

- ^ Steingräber, 9

- ^ Williams, 243; Vermeule, 157–162

- ^ Boardman, 352

- ^ "Terracotta focolare (offering tray), c. 550–500 BC, Etruscan" Metropolitan

- ^ Williams, 242–243

- ^ Ancient Rome as a Museum: Power, Identity, and the Culture of Collecting, Steven Rutledge, OUP Oxford, 2012 ISBN 0199573239

- ^ Pliny: Historia Naturalis xxxiv.16

- ^ Boardman, 351–352

- ^ (Turfa 2005: 55)

- ^ (Richter 1940: 56, note 1)

- ^ a b (Ramage 2009:51)

- ^ (Maggiani 1985: 34)

- ^ (Maggiani 1985: 100)

- ^ (Nielsen 1995:328)

- ^ (Richter 1940: l)

- ^ Grove, 3

- ^ "Opening hours". MARQ Alicante. Retrieved xiv March 2022.

- ^ "The MARQ brings to Alicante the largest exhibition on the Etruscans seen in Spain in the last 15 years". Digis Mak. 20 May 2021.

References [edit]

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Fine art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

- "Grove", Cristofani, Mauri, et al. "Etruscan.", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 28 Apr. 2016. Subscription required

- Maggiani, Adriano (1985). Artistic crafts: Northern Etruria in Hellenistic Rome. Italian republic: Electra.

- Ramage, Nancy H. & Andrew (2009). Roman Fine art: Romulus to Constantine . New Jersey: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

- Richter, Gisela M. A. (1940). The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Handbook of the Etruscan Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Spivey, Nigel (1997). Etruscan Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Steingräber, Stephan, Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting, 2006, J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications, ISBN 0892368659, 978-0892368655, google books

- Turfa, Jean Macintosh (2005). Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1963). "Greek and Etruscan Painting: A Giant Red-Figured Amphora and 2 Etruscan Painted Terra-Cotta Plaques". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 61 (326): 149–65.

- Williams, Dyfri. Masterpieces of Classical Art, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714122540

Further reading [edit]

- Bonfante, Larissa. "Daily Life and Afterlife." In Etruscan Life and Afterlife. Detroit: Wayne Country University Press, 1986.

- ——. "The Etruscans: Mediators between Northern Barbarians and Classical Civilization." In The Barbarians of Aboriginal Europe: Realities and Interactions. Edited by Larissa Bonfante, 233–281. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Printing, 2011.

- Borrelli, Federica, and Maria Cristina Targia. The Etruscans: Art, Architecture, and History. Translated by Thomas K. Hartmann. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004.

- Brendel, Otto. Etruscan Fine art. 2nd edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

- Briguet, M.-F. Etruscan Fine art: Tarquinia Frescoes. New York: Tudor, 1961.

- Brilliant, Richard. Visual Narratives: Storytelling In Etruscan and Roman Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- De Puma, Richard Daniel. Etruscan Art In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 2013.

- Steingräber, Stephan. Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

External links [edit]

- Etruscan Fine art, Laurel Taylor, Smarthistory

- Etruscan pottery from the Albegna Valley/Ager Cosanus survey in Internet Archaeology

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etruscan_art

0 Response to "List 2 Characteristics From the Following Art Erasetruscan Era"

Post a Comment